Discover more from Global Shield's Newsletter

Global Shield Briefing (1 August 2024)

Learning lessons from global emergencies and treating systemic vulnerabilities.

The latest policy, research and news on global catastrophic risk (GCR).

Two irreconcilable truths face us. On one side, we are entering the most disruptive time in human history. Technological, economic, environmental, political, social and biological disruptions will transform the way global society functions – or doesn’t, for that matter. On the other side, we have been unable to learn the lessons from the most recent disruption, COVID-19. This briefing covers this dichotomy. Few countries have performed a thorough review of the government response to COVID-19. And those self-reflective enough to try have recognized how short they came up. Meanwhile, a new UN report conducts a foresight exercise looking out to 2050, and the results are not pretty. Our path winds through a maze of challenges and threats. There is no predicting when, how or why the next crisis hits. Crack open our collective fortune cookie and read the thin strip of paper wedged between these two truths: few countries are truly ready.

Learning the lessons from a catastrophic emergency

The UK COVID-19 Inquiry published its first report on “Resilience and preparedness” on 18 July. It found that “the UK was ill prepared for dealing with a catastrophic emergency, let alone the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic that actually struck.”

Very few countries have completed a detailed review of the government response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Singapore was, as usual, in the lead, conducting a detailed internal review, which formed the basis for a 2023 White Paper on lessons learned. Independent inquiries in both Australia and New Zealand are expected to deliver their respective reports by the end of September 2024. Italy’s parliamentary inquiry, approved earlier this year, will not be completed until 2027. Scotland’s inquiry, which started in 2021, will continue through at least 2025. Canada has not conducted a review, though a citizen-led national review released a report in 2023.

Policy comment: The recommendations from the UK inquiry’s report is all-hazards policy at its finest. Recognizing that the COVID-19 pandemic represents the type of global crisis that countries should be prepared for, the report makes a number of recommendations that would apply to many governments. For example, it recommends a Cabinet-level committee be established for whole-of-government emergency preparedness and resilience, chaired by the leader or deputy leader; a cross-departmental group of senior officials to oversee and implement policy on civil emergency preparedness and resilience; a national risk assessment that assesses a wide range of scenarios for various threats and variations of the same threat; and a regularly reviewed civil emergency strategy. Singapore’s lessons were equally as all-hazards, including increased national resilience, improved public communications, and better institutional planning. The different inquiries around the world also demonstrate the need for regular and proper reviews into national crises. Governments cannot wait years between crises, and then years after a crisis, to begin incorporating the lessons and upgrading policies and procedures.

Also see:

A recent review by the US Government Accountability Office (GAO) – Congress’s audit function for government effectiveness and efficiency – which looks into the lessons from COVID-19 for the federal disaster relief fund. GAO recommends that the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) “identify and document lessons learned related to estimating obligations for declared catastrophic disasters based on its experience with COVID-19”. According to GAO, FEMA did not agree with the recommendation but GAO states that it remains warranted.

Treating vulnerabilities, not just threats

The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) has released a new global strategic foresight report on planetary and human wellbeing. It notes that “The world is already on the verge of what may be termed ‘polycrisis’—where global crises are not just amplifying and accelerating but also appear to be synchronizing. The triple planetary crisis of climate change, nature and biodiversity loss, and pollution and waste is feeding into human crises such as conflict for territory and resources, displacement and deteriorating health.”

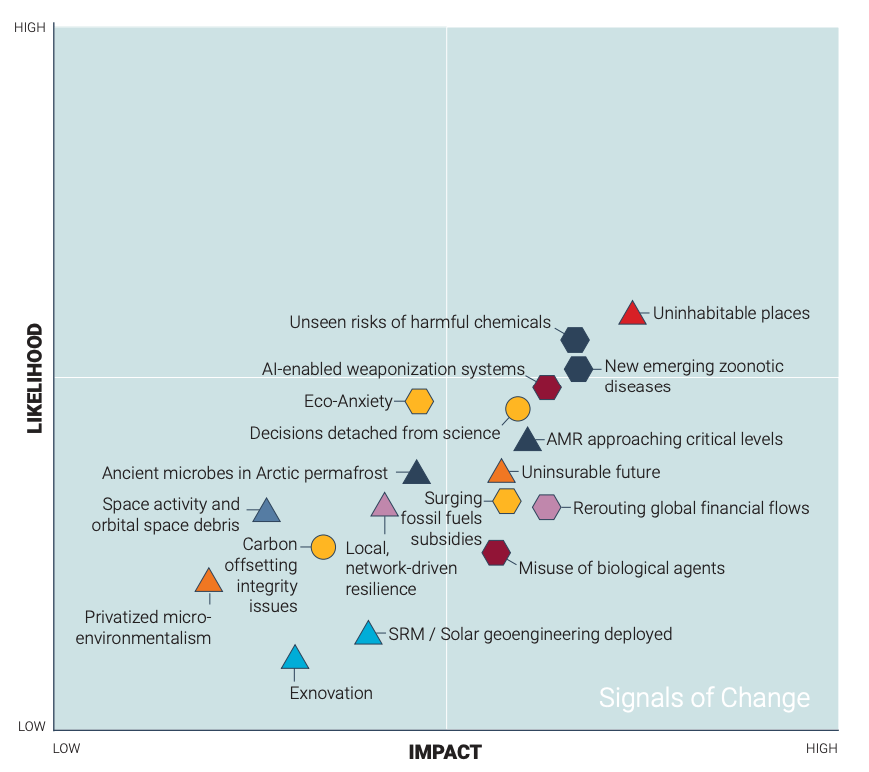

It finds 18 signals of change (see the graphic above), including a number of global catastrophic threats: ancient microbes hidden in thawing Arctic permafrost; new emerging zoonotic diseases; antimicrobial resistance approaching critical levels; unforeseen impacts of harmful chemicals and materials; deployment of Solar Radiation Modification; autonomous and artificial intelligence weapons systems; and new technologies amplify risk of biological agents misuse.

The Cascade Institute has released a paper on strategies for preventing and navigating systemic crises. It notes three broad approaches. First, to prevent polycrises, global systems must be reformed to bolster their resilience and avoid a risk cascade. Second, to respond to polycrises, emergency response capabilities would limit harm. Third, to navigate through polycrises, systems need to be rebuilt and transformed to a state stronger than before.

In an impressive pre-print paper, researchers from the Institute for Environmental Studies in the Netherlands analyzed a database of more than 26,000 disasters over the period of 2000-2018. They found that there were twice as many multi-hazard events (at least two hazards that occur simultaneously, cascading or cumulatively) than single hazard events. These multi-hazard events accounted for 78% of the total damages, 83% of the total people affected and 69% of the total deaths. The authors found that hazard pairs had the same or greater impact than two isolated single hazards.

Policy comment: Global risk is becoming so diffused and complex that delineating individual threats and hazards is increasingly moot. Government agencies and academic fields still think of their issues in siloes. But global risk does not play by these arbitrary constructions. Climate change is a health and economic issue as much as an environmental one. Artificial intelligence is as much a security and democratic challenge as a technological one. Pandemics is as much an economic and social problem as a health one. To deal with global catastrophic risk, policy efforts and supporting expert advice must address commonalities and vulnerabilities across a range of threats. These areas could include: improving international engagement and easing global tensions; strengthening critical infrastructure and the built environment; shoring up food, water and energy supply and security; toughening financial systems and supply chains; ensuring the secure storage and dissemination of knowledge and information; and, building democratic resilience and renewing trust in institutions. Complex and systemic risk means that, almost by definition, we will be unable to foresee a catastrophe or its consequences. Governments need to prepare for all of them collectively.

Also see:

An academic article connecting the fields of systemic risk and existential risk. It provides implications for policymakers, including assessing GCR beyond just a list of hazards, developing adaptive governance institutions, identifying leverage points for reducing GCR, and setting up central offices to own risk and monitor contributors to GCR.

This briefing is a product of Global Shield, the world’s first and only advocacy organization dedicated to reducing global catastrophic risk of all hazards. With each briefing, we aim to build the most knowledgeable audience in the world when it comes to reducing global catastrophic risk. We want to show that action is not only needed, it’s possible. Help us build this community of motivated individuals, researchers, advocates and policymakers by sharing this briefing with your networks.

Subscribe to Global Shield's Newsletter

The latest policy, news and research on global catastrophic risk